Alex Haley changed Black America with "Roots." Now his nephew digs deeper.

The Pulitzer-winning author and journalist Alex Haley was "woke" before there was such a thing. Today, his nephew, Chris, continues his work preserving the Black family tree.

The Pulitzer-winning author and journalist Alex Haley was "woke" before anyone called it that. His nephew, Chris, is continuing his work preserving the Black family tree.

In a voice like the bottom of the ocean, Alex Haley liked to tell the story of how he learned his family's history at the knee of his grandmother, Cynthia, in rural Henning, Tennessee.

Cynthia told him of a west African descendant named Kinte, who had been captured and sold into slavery in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. "She pumped that story into me like it was plasma," Haley recalled in 1977.

Kinte was rebellious, Haley said. He rejected his slave name, "Toby", and tried to escape four times. After his re-capture, when given the choice of keeping his foot or his genitalia, Kinte gave up the foot, and later fathered a daughter, Kizzy, who birthed a son named George who, in turn, had six sons and two daughters, and so forth down the years, until Haley was born in 1921.

The descendants of Kinte, born into slavery, traced a winding path through the antebellum South. They were in Alamance County, North Carolina, when the Civil War began, and it's there where Haley—generations later—found them in a post-war Census, the first to name Black folks as people and not property. Eventually, they moved to Tennessee and, like many freed people in that era, began sharecropping.

Oppression isn't just about domination. It takes not just a people's freedom, but their joy and their sense of self. Many slaves died and went into the ground with no documentation, as if they'd never lived. Slaveholding society perceived them as instruments. You don't remember a shovel after its broken.

Kinte's family, through force of will, made certain that was not them by telling their stories, passing them down like scripture, Haley said. And when, in 1973, Haley collected those stories in a part-fact, part-fiction book he called "Roots," Haley fed a fire in American Black culture.

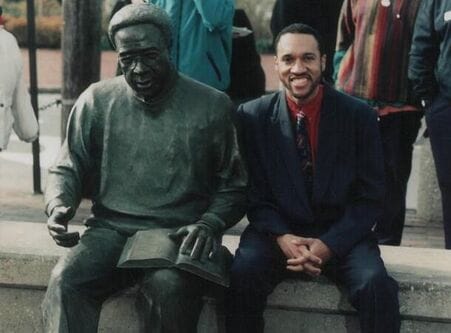

If Alex Haley protected the memory of Black people's lives, Chris Haley preserves the memory of their deaths.

Five years before, James Brown had released a song called "I'm Black And I'm Proud." Black folks, in those post-Civil Rights Movement years, were embracing their "Blackness." That included Black ancestry, even if there was often little documentation of the Black families who survived the brutality of slavery and the "Jim Crow" South.

"In all of us there is a hunger, marrow-deep, to know our heritage," Haley once said, "to know who we are and where we have come from."

With "Roots," Haley didn't invent that hunger, but he gave it a voice. The book won a Pulitzer Prize, became a smash TV miniseries, and Haley—a former Coast Guardsman turned Playboy journalist who'd already left his mark by helping Malcolm X write his autobiography—became a legend among Black folks.

Some of X's ideology had rubbed off on Haley, who spent roughly two years interviewing him. "History is a people's memory, and without a memory, man is demoted to the lower animals," Malcolm X had told a newly-formed conference on Black unity in June 1964, after touring west Africa.

"Roots" wasn't just required viewing in Black homes. When the finale of the eight-part series aired in 1977, it was the most watched show ever. More than half of America watched it.

But that's Alex Haley's story, not Chris Haley's.

Chris Haley also learned his history at his grandmother's knee. He knew of his uncle's work, but had his own plans. He wanted to act and sing and write, and he did.

But Chris, like his famous uncle, drifted to the past. He took a job in the Maryland State Archives, helmed the Legacy of Slavery in Maryland project, documenting the lives of Black families. And, in 2023, he co-directed, wrote, and produced a well-received documentary called "Unmarked," exploring the forgotten or abandoned cemeteries of Black folks.

If Alex Haley protected the memory of Black people's lives, Chris Haley is preserving the memory of their deaths.

It's an enormous task.

'A legacy of racism'

In 1860, just before the Civil War, the Census estimated there were roughly 4 million enslaved people in the South.

But burial practices for enslaved people varied by region. Some plantations had designated burial grounds. Less sentimental owners buried enslaved people under trees and brush because they didn't want to waste arable land. Sometimes slaves were given a marker—a small stone or a plant. Other times, they were not.

That's why finding and restoring Black burial grounds in the South is one part detective work, one part grueling physical labor.

Chris Haley isn't the only one doing this work. In various places in the South, you can find volunteer teams who have begun the arduous task of reclaiming Black burial grounds.

"The thing that's so ironic about who want to eradicate 'DEI' and 'woke' and all that is if you want to eradicate the contributions of Black people, if you want to eradicate the heights to which they achieve, then in many cases you will also be eradicating those white people who assisted them, or who helped them, or who encouraged them."

Chris Haley

In Haley's film, he spoke with volunteers in Virginia who've spearheaded an effort to restore a Black cemetery in Richmond.

"It would make me like sick to my stomach," a woman named Jarene told Haley in his film. She was a descendant of Black folks buried in East End.

"I would come out here with my family, bag up trash, clean off and then we would drive out past the Confederate cemetery that was just like manicured and beautiful all the time," she said. "It was just such a huge disparity visually. This has been a legacy of racism, disenfranchisement and disinvestment."

In the post-war South, oppressed Black communities relied on churches and families to keep their cemeteries. But the brutalities of the "Jim Crow" South made Black communities more poor or transient.

And the white supremacists of the "Jim Crow" era didn't just demand separation from Black communities; they sought to eradicate them, destroying schools, neighborhoods, businesses, and homes when Blacks became too affluent.

Meanwhile, local and state governments poured millions into preserving Confederate cemeteries, but Black cemeteries were left to rot.

There are some signs of change, although even today, many Southern states haven't prioritized preservation with actual money. Virginia is one exception. Lawmakers passed a bill in 2017, and expanded it in 2018, to spend state money on historic Black cemeteries, but that's just a start.

I recently spoke to Chris Haley about his work, his lineage, and what it's like continuing his family's work during a political backlash against teaching the history of racism in America.

The Living South Conversation

The following is a transcript of my conversation with Chris Haley. It has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The Living South

So first off, Chris, tell me a little bit about yourself and, where you're from, how you came to be interested in the work you're doing.

Chris Haley

I was born in Washington, D.C. and my initial passion was the arts as in singing and acting and writing, and within that, I'd say very early on, I became very interested in African American history and Black history. My grandmother gave me a book, which I think was called the American Heritage History of the Negro in America, so that tells you by that terminology, it was an old book that she gave me.

And I was just fascinated because it showed so many pictures of historic Black people I'd never seen before, because I only knew, let's say the classic top ones, which is Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, George Washington Carver, and perhaps to some degree, Charles Drew.

So those were it. And so when I looked at this book and I saw all these other faces of people who were accomplished enough to be in a hardback book, which wasn't a comic book, about their accomplishments, that put it into my mindset. Along that time, I think I was aware that my uncle was a writer and I was aware that he did interviews for Playboy magazine.

And so within that, I knew he was talking to a lot of influential people, really heady people. I did not know to what degree he was or was planning to do anything about Black history and certainly did not get a sense that he was doing something about our family specifically.

I was always interested in history. And as I got a little bit older within the outlook of the arts, I started thinking about putting together in some way, whether as an actor, a producer, a writer, projects about Black history, biographical figures, people who actually lived and died and contributed to the Black American experience.

And that brought me to the Maryland State Archives. My uncle had found one of his pivotal pieces of connectivity to the Kunta Kinte story from a Phoebe Jacobson, who was the head of research there, who helped him find a 3x5 index card that listed a ship, which approximately matched the timeframe that he believed Kinte would have arrived in Annapolis, Maryland.

She got me in touch with the state archivist and I've been there for 30 years now being the director of the Legacy of Slavery in Maryland project.

It really was the old school view of genealogy, which was not Ancestry.com or FamilySearch or pulling up a website and connecting all the dots on your electronic family tree, it was, literally, you talk to people, you take your notepad, you take your tape recorder, and you travel, you go to where they are, actually go to a cemetery and look at the gravestones of your ancestors.

Even in our own lives, you more than likely have that sense of connecting a gravestone or a grave site with your history, with your grandparents, with your great grandparents, with people you've never seen but you've been told that they are related to you.

That's what pushed me to actually go to Georgia, because I was looking at my mother's side, and actually trying to find cemeteries around the churches where her grandparents and her parents and my great grandparents lived, and where they worked, and the people with whom they socialized.

Shiloh Baptist Church in Augusta, Georgia, I went there and I literally just trod the grounds and found the graves of my great grandparents side by side. And their brother and sister, both of their brother and sister who married each other.

I think that was probably the start to my appreciation of cemeteries as being one of the fundamental tangible steps you should take if you're trying to do genealogy.

I think you have to go to see where that gravesite is. Not only to see where they have been laid to rest, but if there are any other people laid to rest close to them, that might give you a clue because of their last name, because the date of their passing, that this might be somebody else who's related to you.

When Brad Bennett contacted me when he had put a movie forth for the Utopia Film Festival, where I was executive director, when he mentioned this movie project to him, I thought, yeah, how can I not be aboard?

The Living South

Almost like detective work.

Chris Haley

It is, it absolutely is. And I think for those of us who know that, then we appreciate going to cemeteries today and you appreciate seeing where people are laid to rest.

You appreciate if there's any life dates there, and you appreciate who's buried next to them. You literally do because more so than now, back in the day, people did tend to have family plots or places where most of their immediate family and those close to them would be buried.

And perhaps it was for racial segregation reasons where there weren't other places they could be buried. Maybe it's they pooled their money together or maybe it was a conscious choice that in life we were together and in the afterlife we want to be together too. So we are going to put our coins together and buy these plots, which as much as possible, keep our family together.

My great grandmother was born I believe in 1893, and my great grandfather, I think he was nine years older than her.

The Living South

So these are folks who lived through some of the most brutal Jim Crow years that you can find in Georgia. And what is it like for you to be there on this?

I know for most folks, it's a spiritual feeling when you're looking at your ancestors, I feel like it's different for folks who've lived through such times and they are your descendants.

Chris Haley

I know more of my great grandmother's story. She was of mixed race, as was her sister. She was born of a union that could not be legalized. My great grandfather was white, my great grandmother was Black.

His name was Charles Fulcher. My great-grandmother's name was Lizzie Hankerson.

She was listed next door to him and another single dwelling with her two mulatto children, whose names were Ida and Bertha, which are the names of my great-grandmother, and my great aunt. So even in that alone, I could see that it indicates that they were a couple as much as they could be a couple and they lived as a couple. So even in this census record, it appears that perhaps they could not say that they were man and wife because they couldn't get married. It was illegal in Maryland, literally until 1970, 1973, I think. It's when the loving decision happened. It's the same thing in Maryland. So God knows in Georgia, it was the same thing. I also found out later that my great grandfather did hang out, did socialize, with his great grandson, Buddy, whose real name was Thomas, who died when he was nine.

I understand they used to go fishing together, and that he really recognized and loved his grandson.

Respect and appreciate that they really had a connection as much as they could at that time.

How many times when we're a kid, do we really engage our parents and our great grandparents about their lives when they were kids or about their lives growing up? You just don't do it. For one, you're not truly interested because you're playing.

You're out there playing with their friends. You have to go do your homework. And maybe some of these things are so challenging quite frankly, painful that they're not going to say it to a little boy. They're not going to share, because for one, they'll have to push it probably so hard to get that little boy or that little girl to understand just how deep that situation is.

Because a simple question could be why didn't you marry great grandma? Because she was Black and I was white. What does that mean? It would be so challenging to get a child to understand that. So you don't try, you just are who you are.

The Living South

As a parent of small children, sometimes I'll talk about the worst parts of the South in our history and it's amazing to me how, without any preparation, they get to the right and the wrong of it really quickly.

One thing I wanted to ask about: People have the false impression of the Jim Crow era as a time when white supremacists were just looking to keep people separate.

That doesn't quite sum it up because those white supremacists also tried very hard to eradicate Black culture and Black communities and families, almost like erasing a Black life and then you think about these unmarked graves and these poorly kept cemeteries, it's like erasing death too. They're not even there. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Chris Haley

I think part of the reality that comes to someone who's doing genealogy or family history, there's this aspect of resentment and envy and jealousy that goes on within the Jim Crow era and frankly is going on today:

I don't want you to do well because part of my superiority is based on my belief that you are lesser than me. You cannot achieve to the degree that I can achieve. So if you have a flourishing Black Wall Street, if you have Tulsa, if you have Greenwood, if you have places that are so amazingly affluent and they're Black- run, then that eradicates my justification for why I can treat you so badly, for why it was right and Christian for me to enslave you.

Because you were beasts, you were savages, you could not have done anything worthwhile without our keeping you under heel to teach you, to mold you, to show you how to do it. So If you grab by your own bootstraps and build a town, which is thriving, then that defeats my, ethos.

How can I continue to justify how I treat you and how I think of you if you're doing things which are better than many of my kin folk are doing? So that is, I think, an absolutely pinpointed part of why the eradication of the appreciation of gravestones, of the histories of free and enslaved Black people is fought against to this day.

The thing that's so ironic about who want to eradicate "DEI" and "woke" and all that is if you want to eradicate the contributions of Black people, if you want to eradicate the heights to which they achieve, then in many cases you will also be eradicating those white people who assisted them, or who helped them, or who encouraged them.

The Living South

I live in Durham, North Carolina, which was the home of "Soul City" and a once-flourishing Black Wall Street, and a lot of that history here in North Carolina isn't often talked about. It's that way across the South.

Chris Haley

I think it's important, for all people, Black, white, brown, red, yellow, pick your crayon to explore what the contributions of their heritage has been. and that extends beyond, but also includes your specific line, which is to say what did your mother do? What did your father do? What did your grandparents do? What did their mothers and fathers do?

If you're born into the royal family, and you're William or you're Charlotte, your whole life is being a prince or a princess. All you know is that your grandmother for the longest time was the Queen of England. All you know is that your father is the Prince of Wales. That's all you know. That's your day to day life. And that's where your life begins. Your history starts telling you that there's more to it, that it has a grander scope and a grander meaning.

One of the main things I tell kids, is that there's two documents which have made you historic already. I say that's something called a birth certificate. It's something called the federal census.

Those two documents are something that you are on and they will be here after you're not here.

You are a historic point in time. Years from now somebody will be sitting in some library at home and they're going to pull up some document and there's going to be your name on it and your birth date on it and that is history. And that is your history.

You are already a part of history. You are literally a part of history because you were born and you lived and you were on at least this one document.

The Living South

Your uncle, of course, was a very important journalist and writer, gifted writer, and asked questions and told stories that, frankly, not a lot of people were telling in his era. Do you see yourself as, being part of that lineage? Does that inspire what you're doing right now?

Chris Haley

I would say from the genealogical point of view, definitely.

The Black history point of view or that, that path was already a part of me, but the genealogical point of view, I definitely see that. I don't know if I would have embraced it so thoroughly and so passionately, if it wasn't for what he had done.

My mother had something to do with it too. And so that made me think I really should, because I do appreciate genealogy and respect it, I should look into her background and into her history because that would be my roots, so to speak, and to look at my mother's family and my mother's father's family.

So it could very well be that if it weren't for the fact that roots Was as huge as it was and so I might not have ever gotten to the point where I started to think I should start doing this myself. I should start respecting my mother to the same degree as much as possible as Uncle Alex respected his mother.

For me to deny it would be crazy.

If this really touches you and if this is really something that you feel is important, then I would encourage people to perhaps see if there's volunteer organizations in your area that are and or have taken up the mantle of just cleaning and pruning different cemeteries in in that area or old churches where there's parishioners of hundreds of years ago who are there, and and volunteering. Maybe once a month you'll go there and you'll mow the lawn or you [00:17:00] will take out the weeds.

There's no way you won't feel better. I mean, even if, and again, if nobody, you may not know a soul in that, it may not even be your family, but you will feel better after you've done that because to whatever level of spirit, spirituality that you might have, you could think they're looking down on you and they're happy.

And if weren't really that great a person, they're looking up at you.

It should mean a little bit to everybody, because if your life means a little bit to you, if your life meant a little bit to somebody else then you should appreciate this other person who also lived. Because in appreciating them, I really truly believe you have to look in the mirror and say, I appreciate them, so I have to appreciate me.