For some, Bakari Sellers is the voice of the resistance to MAGA. But his fight goes back much farther than Trump.

South Carolina native Bakari Sellers has become one of the most cogent anti-Trump voices in America. Here's how his roots in the Civil Rights Movement prepared him for this resistance.

Bakari Sellers is one of the most polished people you will ever meet. In person, he cuts an imposing figure. He's tall, lean, and well-dressed. But in May 2020, when the world felt like it was ending in more ways than one, Sellers' cool finally cracked. He was crying on national television.

He wore a suit and tie, but looked like he hadn't shaved in a minute. His eyes were red. His voice was hoarse. A CNN anchor asked him questions as Sellers—a nationally-known civil rights advocate, former South Carolina state lawmaker, author, and political analyst—blearily rubbed his eyes. It was the thick of the pandemic, and days before, a Black man named George Floyd had been murdered on a Minneapolis street with a white police officer's knee on his back and neck.

A cellphone video captured Floyd's final moments, pleading for air and then for his mother while a police officer pinned him to the ground for more than 9 minutes.

Want to support The Living South? Sign up for a $4 monthly paid subscription (and receive an audio version too!).

Floyd's killing sparked riots across the United States. The Civil Rights Movement was 50 years past, but his death was a reminder of an enduring truth—that Black folks in America are several times more likely than white folks to be killed by police officers.

Civil rights advocates tend to assess their 'wins' and 'losses' over generations, not in single moments. But even for people built in the movement—and Sellers, the South Carolina-born son of a civil rights hero, is definitely one of those people—Floyd's long, slow murder in broad daylight made the struggle feel eternal, Sisyphean.

"You get so tired," Sellers told CNN. "We have Black children. I have a 15-year-old daughter. What do I tell her? I'm raising a son. I have no idea what to tell him."

Sellers was trying to explain Black grief to the nation—the idea that Black folks, linked by a shared lineage of injustice—can empathize deeply with another Black person's unjust murder, can feel it almost as if they've lost one of their own family.

Black people "share a kinship of calamity," the historian and author Jemar Tisby wrote of Black grief in 2020. "A brotherhood and sisterhood of suffering. Like any family, it is not something we choose."

There's a part of this country that will never truly understand that, try as hard as they might, and there's a part of this country that doesn't want to. White Americans might have shared in a collective grief of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, but even then, there was a feeling that the perpetrators would get their comeuppance, something Black folks rarely get in American history.

Yet here was Sellers trying to explain it all to a white anchor on CNN in 2020. Six days before Floyd's murder, Sellers published his memoir, "My Vanishing Country," an elegant portrait of working-class Black life in the rural South that would become a New York Times bestseller.

He might have been celebrating if not for the grim circumstances. Instead, he was sitting in his home in Charlotte, N.C., speaking into a laptop, trying to explain an unexplainable feeling. "It's hard being Black in this country when your life is not valued," he said.

"Every time your phone rings, you're concerned about what's going on. They came home the other day and said they had an active shooter drill at their school. You look at kind of how racism has become en vogue again."

Bakari Sellers, on being a parent in 2025

The Voice of Resistance

For the millions of viewers who tune in to watch CNN each week, Bakari Sellers has become one of the most recognizable anti-Trump voices on the network.

He is clear and cogent, punchy when other liberals are mealy-mouthed, urgent, and beholding to a big picture that comes from being raised in a resistance that's much older and deeper than this one. Joy-Ann Reid invoked no less than Toni Morrison in praising his 2024 book, "The Moment," an unsparing account of "the racial reckoning that wasn't," as the book puts it, after George Floyd's killing.

Sellers' book feels prescient, with some of President Trump's top allies reportedly pushing him to pardon Floyd's killer, ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who was sentenced to 22 years in prison for Floyd's death.

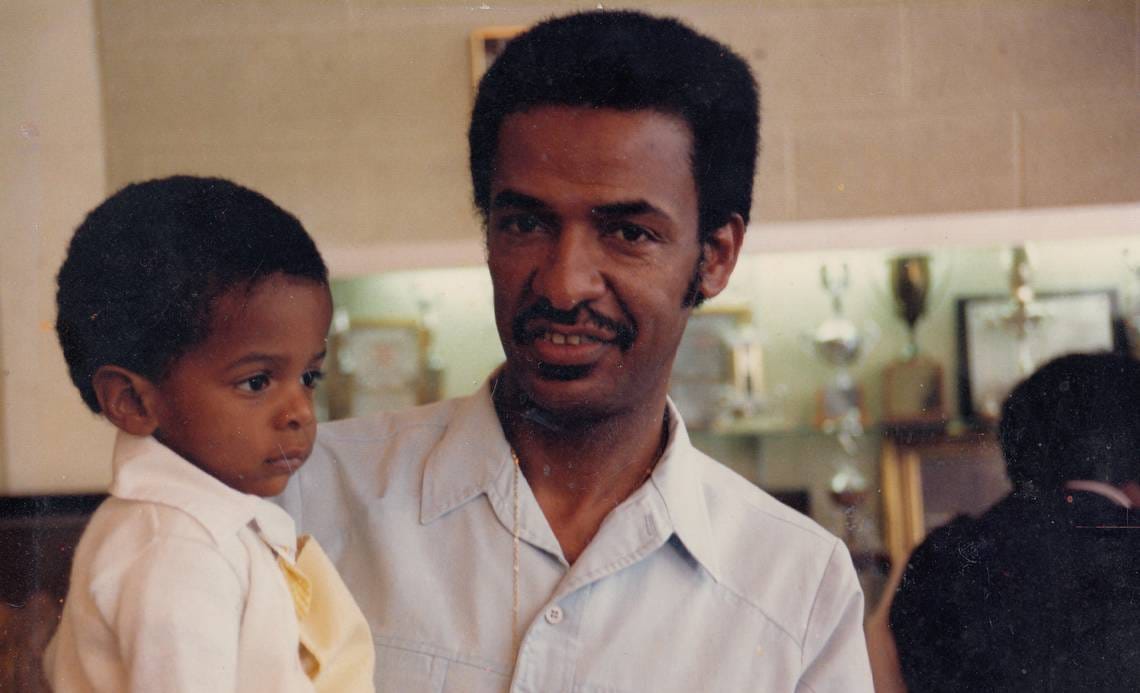

To understand Bakari Sellers though, you need to understand something that happened 16 years before he was even born, something Sellers once characterized, nevertheless, as the most important day in his life.

In February 1968, Sellers' dad, Cleveland, was shot in Orangeburg, S.C., as state troopers fired into a crowd of unarmed Black students. The students were protesting a local, "whites-only" bowling alley.

The campus shooting, which came to be known as "the Orangeburg Massacre," left three Black students dead and injured dozens more.

In the early 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement had won victories desegregating places like Greensboro, N.C., with peaceful sit-ins, but in 1968 white people had grown impatient or hostile toward the movement, especially as the war in Vietnam lingered. Martin Luther King Jr., who had recently criticized the war, was an increasingly unpopular figure. He'd be dead before the summer.

And demonstrations like the one on South Carolina State's campus in Orangeburg were characterized by tense interactions with local police, who had already broken up one mostly nonviolent demonstration in front of the bowling alley by beating students with clubs.

Most of the students wounded in Orangeburg were shot in the back as they ran away from the gunfire. Nine law enforcement officers were brought up on charges by the US Justice Department, but none were convicted by a South Carolina jury.

Yet Sellers' dad, a 23-year-old student at South Carolina State, was known by the police because of his previous involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the primary youth protest groups in America at the time.

So Cleveland Sellers was charged and convicted of instigating a riot. He was the only person convicted of anything involving the Orangeburg Massacre.

Decades later, South Carolina pardoned Cleveland and Gov. Jim Hodges apologized for the shootings on behalf of the state, but in 1968, the shootings were poorly covered by the mostly white press. One Associated Press report falsely claimed there was an exchange of gunfire, but none of the protesters were armed.

Sellers, like so many Black people in this country, especially Black Southerners, were raised on these injustices, knew them intimately.

When generations of experience tells you that the system doesn't work for you, you don't put faith in appeals to that system. Some Black Americans cannot be as shocked by the corruption of Trump, or any politician for that matter, when your people have suffered at the hand of corruption for centuries in America. It's not cynicism if it's real.

All of this might make Sellers as suited for the role of speaking for "the resistance," or whatever you want to call it, as anyone in America. After all, he's been resisting since before he was even born.

"I believe George Floyd's death for a lot of us was the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back," Sellers wrote in his 2024 book.

"George Floyd's death may be un-American," Sellers continues. "It may be unbelievable, heartbreaking, tragic. It may be every adjective that you can think of. But it's not new."

"I feel like journalists like yourself are finally not allowing the world to push them around and say, 'Look, we have a role.' I think journalism is on its way back."

The Living South Conversation

I struck up a connection with Bakari Sellers in 2021, after deputies in my North Carolina hometown shot and killed a Black man named Andrew Brown who was trying to flee from arrest in his car.

Sellers, an attorney, was there to help represent Brown's family, as were many other civil rights leaders in the South.

No law enforcement officers were charged in Brown's death. And so everything old is new again.

This week, I spoke to Sellers for a brief but far-reaching conversation about his history, where we're headed as a country, his family, his daughter's life-saving liver transplant in 2019, and what's making him feel optimistic.

The following is a transcript of that conversation. It has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The Living South:

First of all, I see you almost on a daily basis on CNN trying to unpack our unpackable world.

How are you staying on two feet? How are you doing the job right now?

Bakari Sellers:

My kids keep me the most humble. And watching two amazing little twins run around the house with the youthful naiveté they have makes you get that warm feeling that you just wanna make this country and in particularly the South, a place where they can live and grow and be happy and healthy and maybe not have to worry about some of the same things my father did or I did growing up, and be able to truly be free.

The Living South:

One of the things I've heard you say before, and I've certainly thought about this as someone who came from a rural Southerner's background, is that there's a perception when you get out there, sometimes still to this day in the year of our Lord 2025, that Southerners are bumbling idiots.

How do you think we're doing, Southerners, in terms of dealing with that perception?

Bakari Sellers:

I think we're fine. As long as my friend Mark Sanford stays off the Appalachian Trail, I think that we'll be just fine.

You're starting to see some people emerge on the national scene from the South, both on the right and the left. People like Stacey Abrams. You have some up-and-coming individuals like the Jeff Jacksons of the world. And so I think the South is just becoming more refined, articulate.

The question is: Are we forward-looking enough? That's always been my biggest concern about being raised in the South and people having this really weird nostalgia for yesterday. But with places like the Research Triangle, places like Charleston, South Carolina or Atlanta, Georgia, we can really be the hub for what tomorrow looks like.

I just don't know if we have that vision in place.

The Living South:

What's it gonna take to get that vision in place? What does that require?

Bakari Sellers:

A new generation of leadership. For each one of those names I named of young, kind of new leaders of the future of tomorrow, the Josh Steins of the world, we still have a considerable amount of age on us in our state legislatures and in our United States Congress.

We have to be willing to turn the page on both sides.

The Living South:

You're a father. I'm a father. There's certainly a lot of anxiety out there, in general, but I've heard this line of thinking before, that it's a particularly hard time to be a parent, to deal with climate anxiety, to deal with the gun violence, we're afraid of World War III, we're afraid for our democracy.

How do you as a parent deal with that?

Bakari Sellers:

I don't know. We've actually gone through the transplant process too with our little girl. So we've been in and seen some of the best and brightest facilities we have in the country. I'm talking about Duke right now.

And every time your phone rings, you're concerned about what's going on. They came home the other day and said they had an active shooter drill at their school. You look at kind of how racism has become en vogue again.

Outward ignorance displayed by some and you wanna shield them from that. All in all, we just try to fill our home with love because we know when they leave those doors, that's something they may not get.

The Living South:

Yeah. I notice this with my children. I don't think that they pick up on the pessimism that adults are feeling, or if they pick up on it, they don't carry it with them.

Bakari Sellers:

They don't carry it with them, and their bad days are usually because mommy and daddy didn't put a snack in their bag. So relatively speaking, I think we're doing all right so far.

The Living South:

You're the child of a civil rights activist. You've been a civil rights activist. How do you see that long, slow arc of social justice bending right now, that Dr. King talked about, that Barack Obama brought back into the consciousness with his speaking? How do you see it?

Bakari Sellers:

I feel like we're going backwards. The attacks we've had on DEI, the attacks we've had on institutions of higher learning, particularly HBCUs, et cetera. I look at those things and it feels like we're right before Brown vs. Board of Education. And we just have to, every time we're on the precipice of a period of reconstruction, we take steps back.

That always happens. We saw it after Brown v. Board and we've seen it recently after George Floyd. There's still a lot of fight, a lot of meat on the bone left. Because those individuals who are allowing their ignorance to develop their policy are driving the train.

And so the rest of us have to hold on and hope that over the next couple of years, we can have a better America.

The Living South:

Yeah. Anger is something I know a lot of people are feeling right now. My wife's a therapist, so I hear her say that anger can be productive, but it can also destroy. You have to talk about this stuff on a daily basis. How do you balance that feeling of frustration with where we are, with vision for where we're going?

Bakari Sellers:

I'm at peace. I don't have that frustration. I'll continue to raise my voice, but I just try to love on my wife and love on my kids and just stay away from that frustration because a lot of times that frustration or anger can become paralyzing.

The Living South:

And what do you say to people who are feeling paralyzed, who say, maybe it's healthy to tune out a little bit right now?

Bakari Sellers:

It's good. I think that you have to say particularly now, it's so much stressors in the world, so many stressors in the world. I think about just social media and the things that our children have to go through. You and I didn't have to go through.

I can't imagine having Snapchat or Instagram when I was in high school. I might not be here today.

I just think about all those pressures externally. It's always good to just take care of yourself sometimes.

The Living South:

What do you look out there and see right now in the South and say that makes me feel optimistic or that makes me feel inspired? What is that for you?

Bakari Sellers:

I feel like journalists like yourself are finally not allowing the world to push them around and say, 'Look, we have a role.'

Speaking up for that role of journalism, particularly telling the stories not on CNN or MSNBC, on Fox News.

But you're really driving the narrative in those respective cities and municipalities and local governments, and you're able to truly effectuate change like that and you're actually able to touch a voter and have that trust with that voter more so than anybody else. I think journalism is on its way back.

The Living South:

That's inspiring to hear. Who's your hero, Bakari? Who inspires you?

Bakari Sellers:

Probably say (my daughter) Sadie is my hero. I would always say my daddy again.

My daddy is always gonna be my one of my heroes, but Sadie, my daughter, is probably the strongest woman I've ever seen in my life. Going through a liver transplant at 10 months old and being here today at 6 and still doing extremely well with no modifications or anything.

It is just, it's fascinating to see.

The Living South: I wish you and your family well and I hope everything goes well for Sadie.